AIDS: The Lost Voices

Republic of Ireland:

MOUNTJOY &

ARBOUR HILL

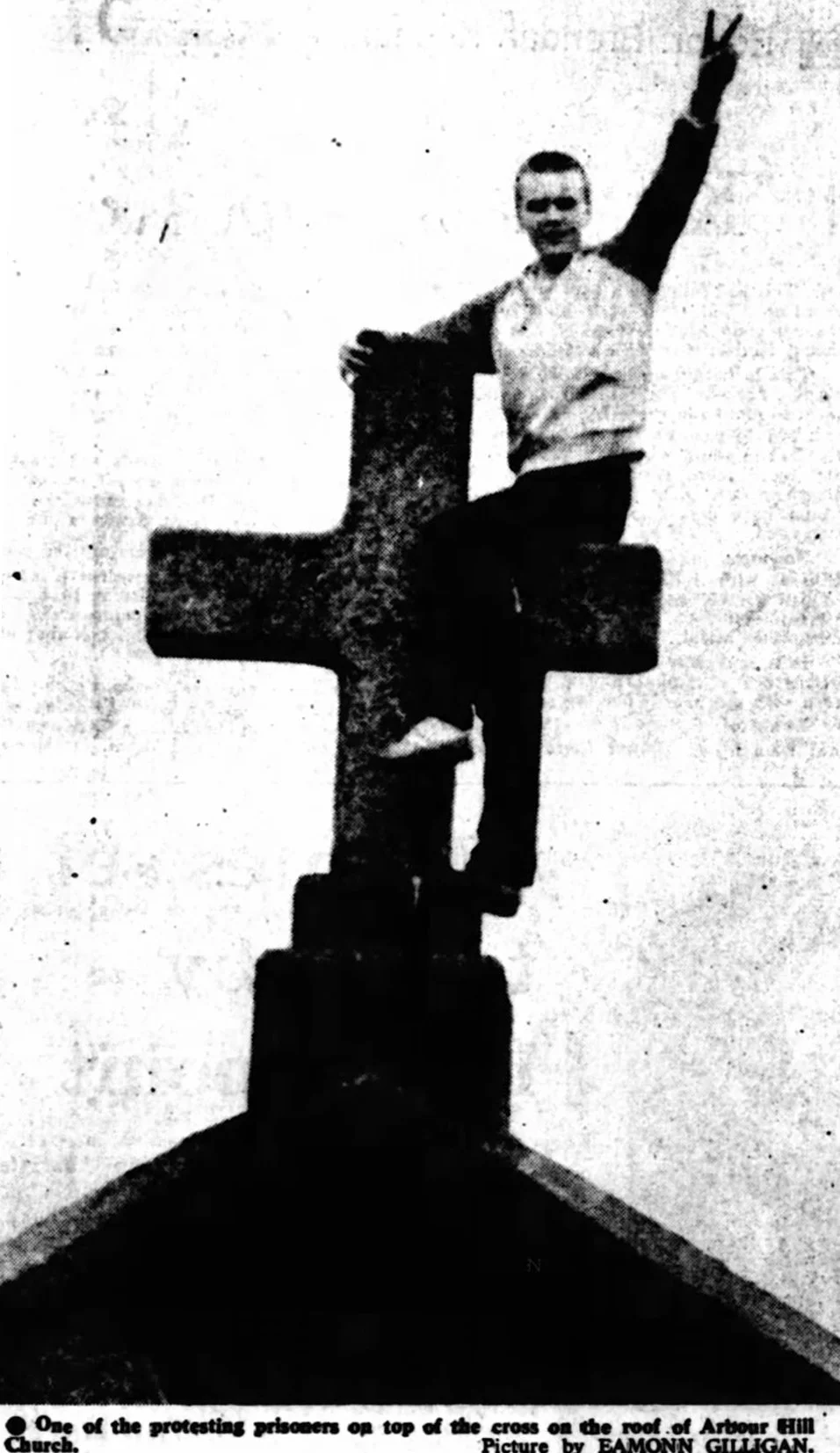

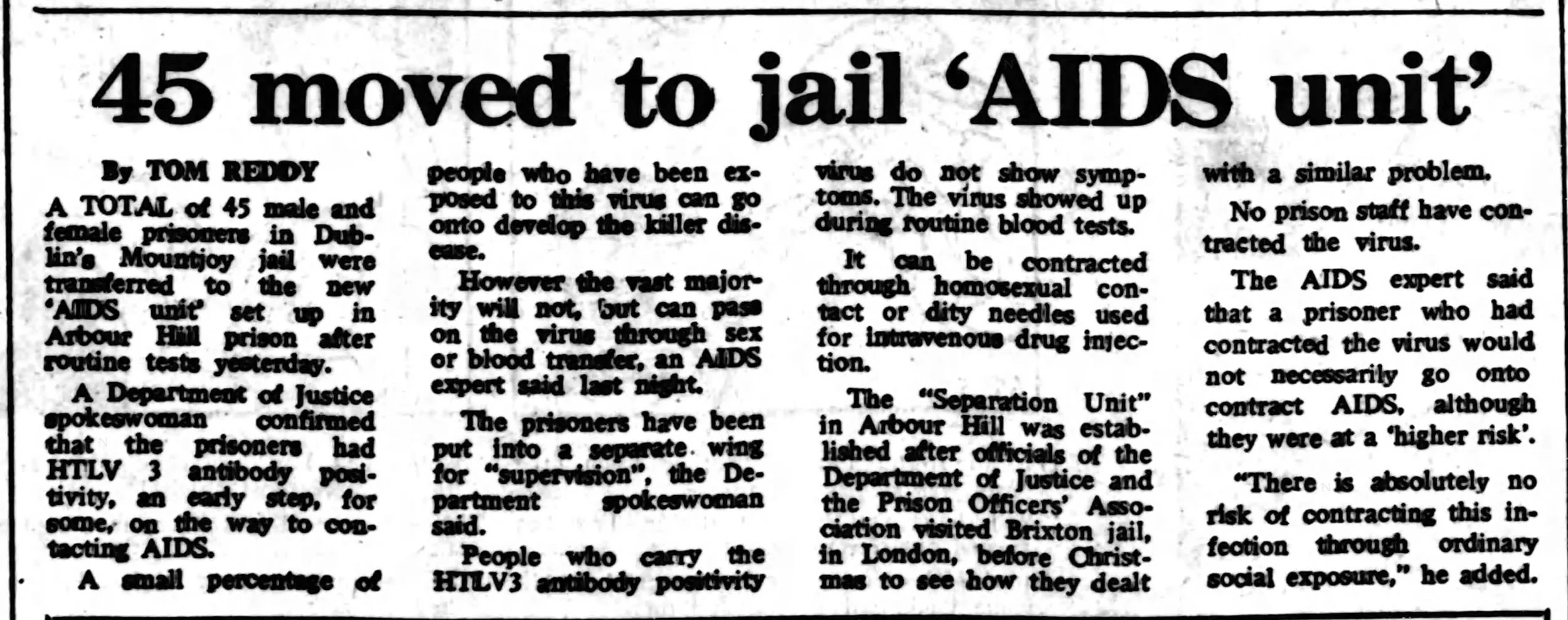

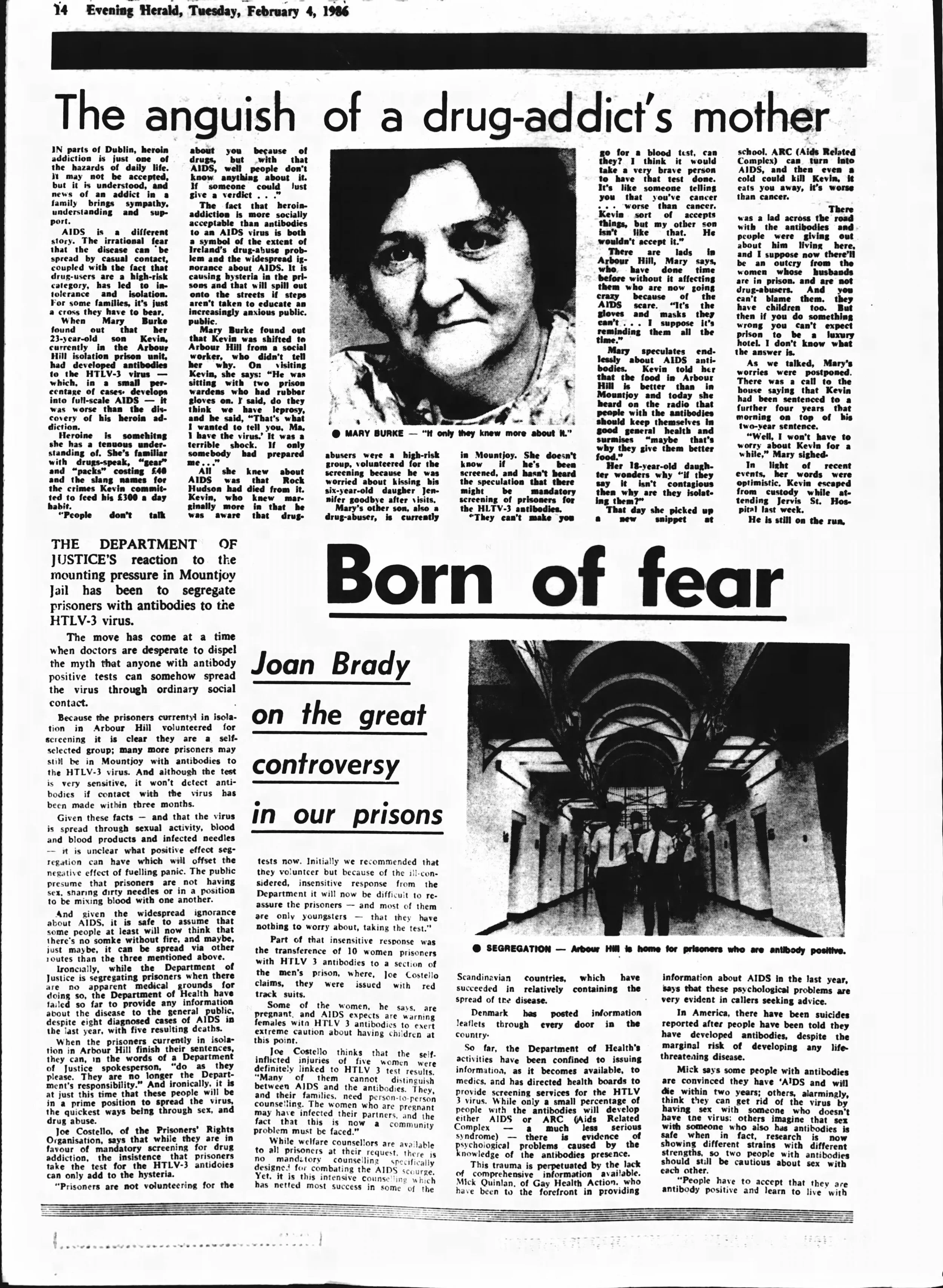

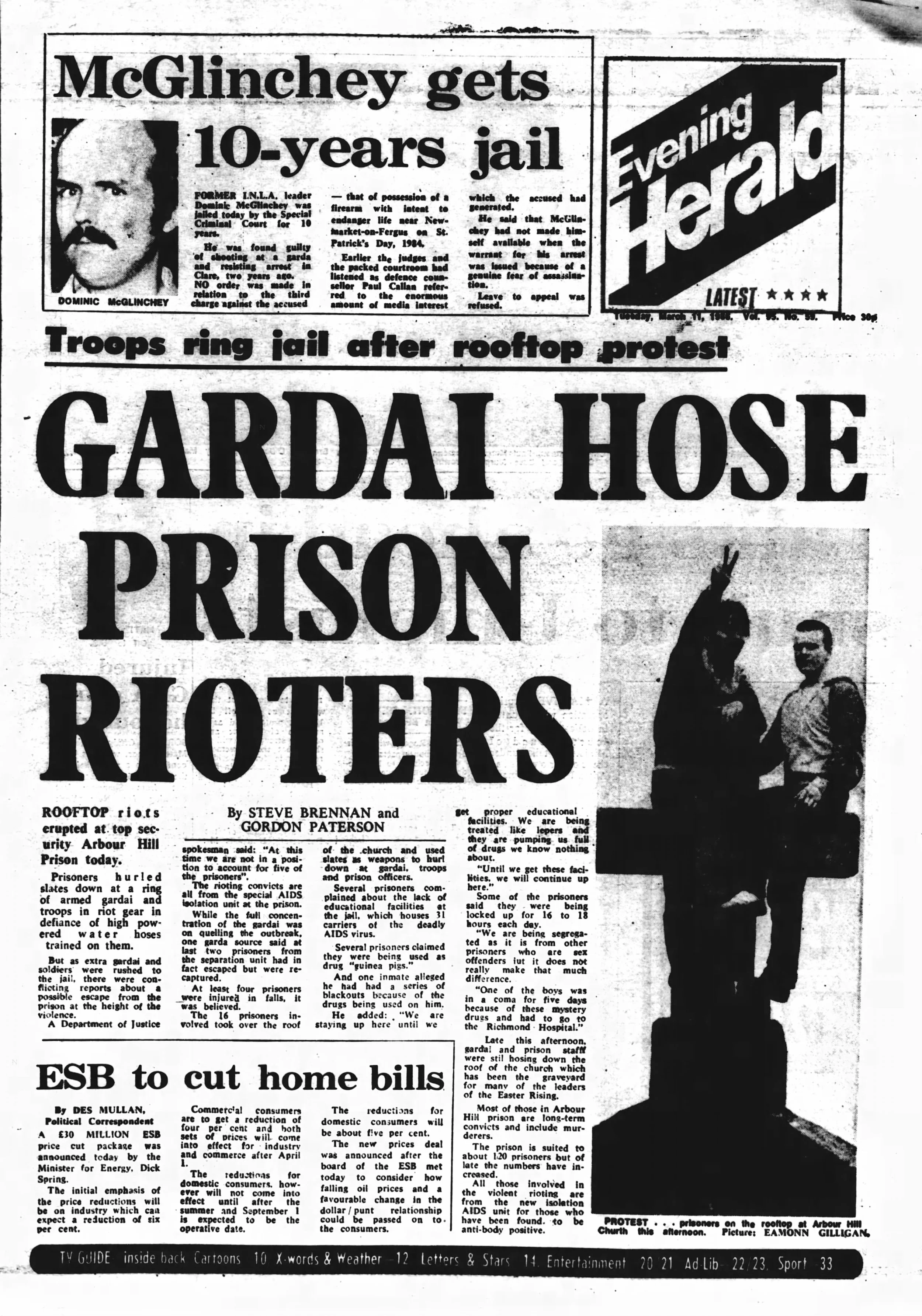

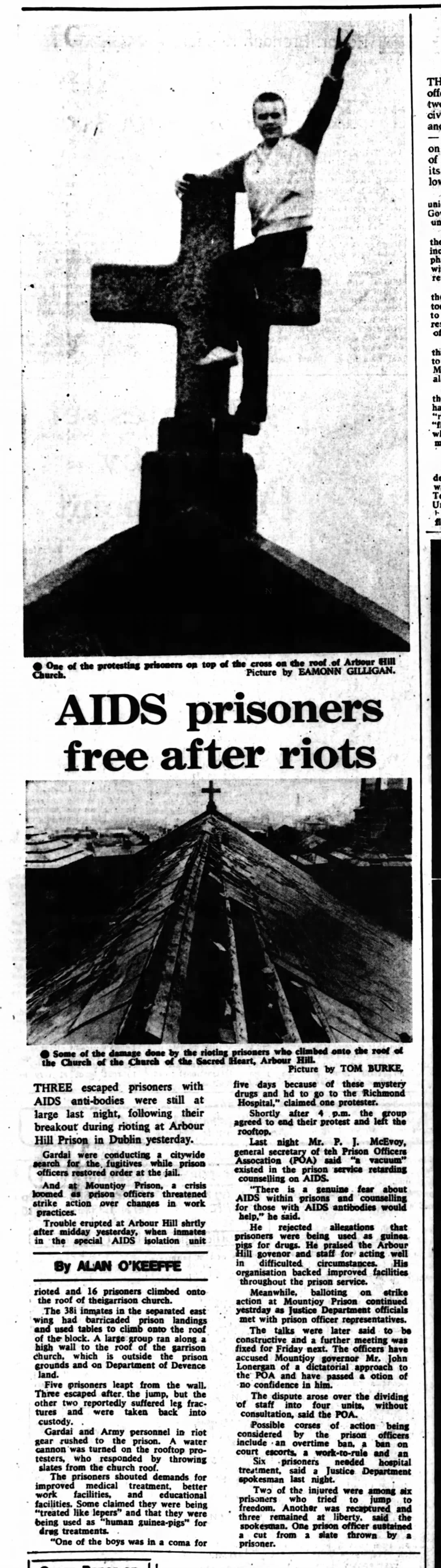

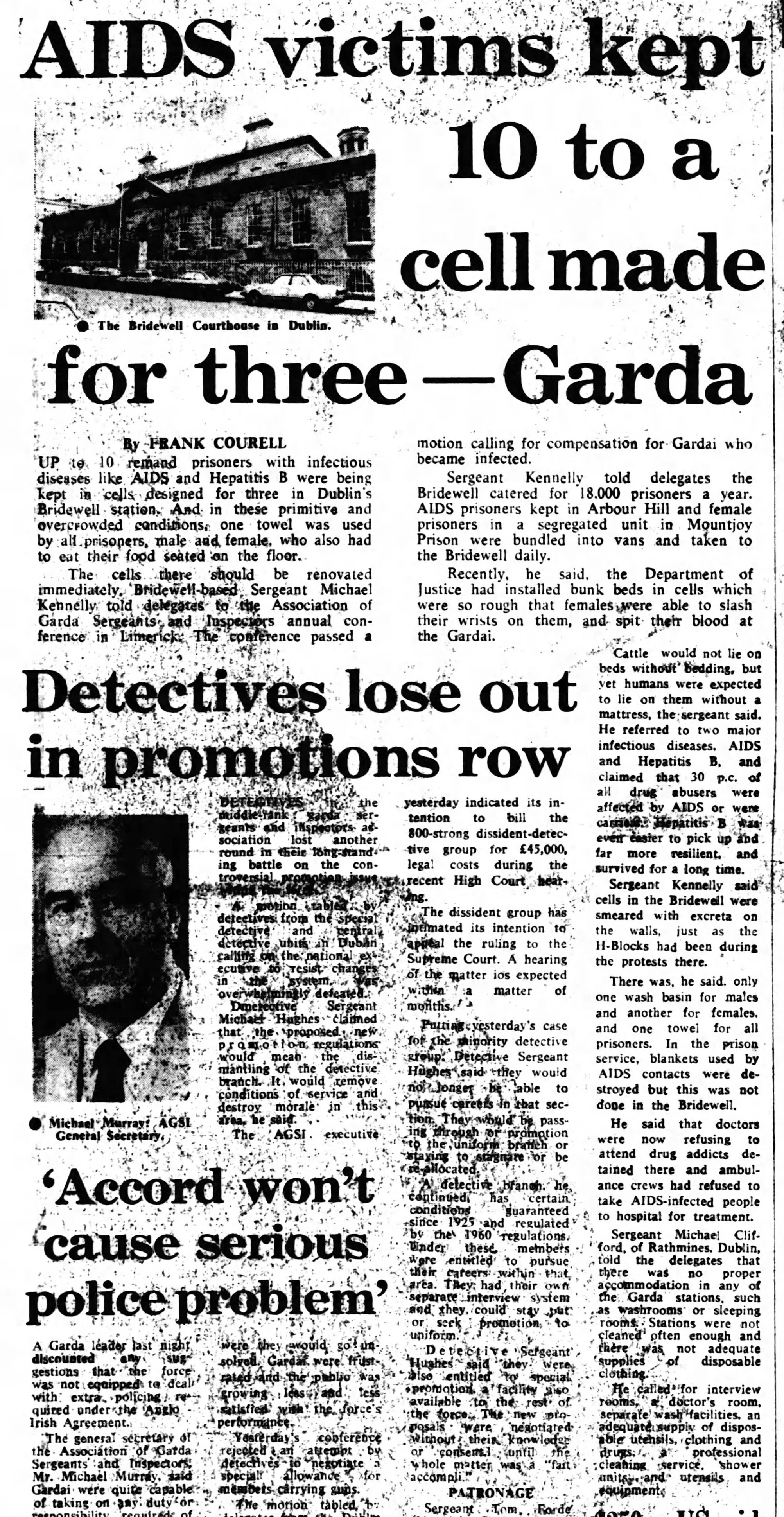

In 1986, Dublin’s Mountjoy and Arbour Hill prisons opened separation wings for inmates diagnosed with AIDS — a policy prisoners likened to being “treated like lepers” that sparked a wave of desperate protests: dirty protests, prolonged sit‑ins and rooftop demonstrations that only drew sustained media attention once visible, dramatic resistance began. Men and women confined to segregation described humiliating conditions — paper pillowcases and sheets, food served on paper plates, exclusion from work and education, and strict prohibitions on mixing with others — measures that compounded the isolation of illness and drove three men to escape while prompting public acts of defiance that forced the outside world to confront punitive, fear‑driven policies behind bars.

The punishment for their crimes was a prison sentence, not an HIV/AIDS diagnosis, yet by standing up, using their voices and exercising their right to protest they exposed inadequate medical care, entrenched stigma and human rights abuses in the prison system. In doing so they became unwitting activists: their resistance helped secure improvements in conditions and access to treatment for incarcerated people living with HIV and warrants recognition in the history of AIDS not only for their offences but for the role they played in advancing dignity and humane care.

Part 1

Part 2

RTÉ is Ireland’s national television and radio broadcaster, and its online archive holds a vast collection of television clips documenting how the broadcaster reported on the AIDS pandemic as it unfolded. We have shared some of these audio clips in this podcast episode, but you can watch the clips and many more by following the links to their website below.

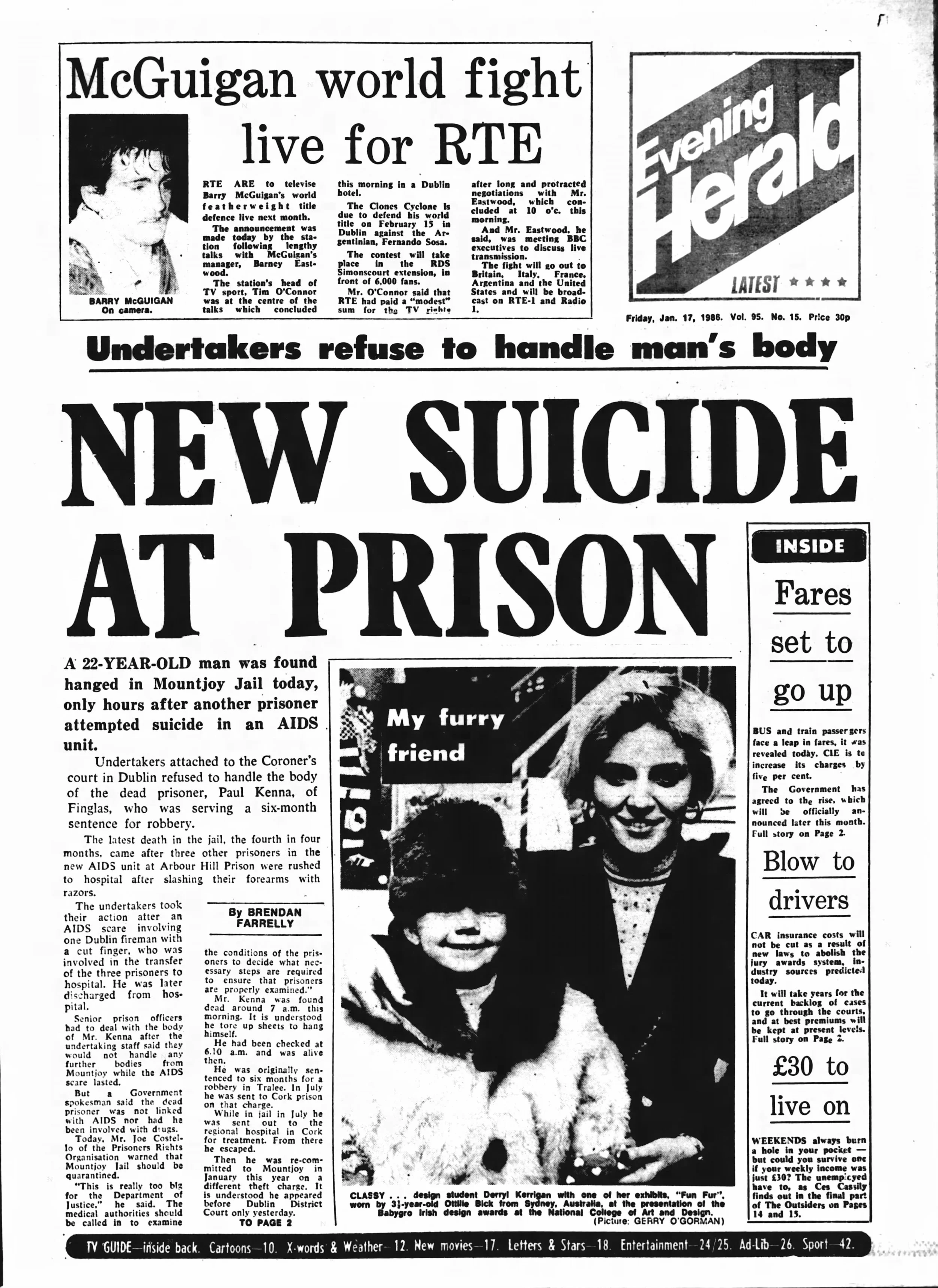

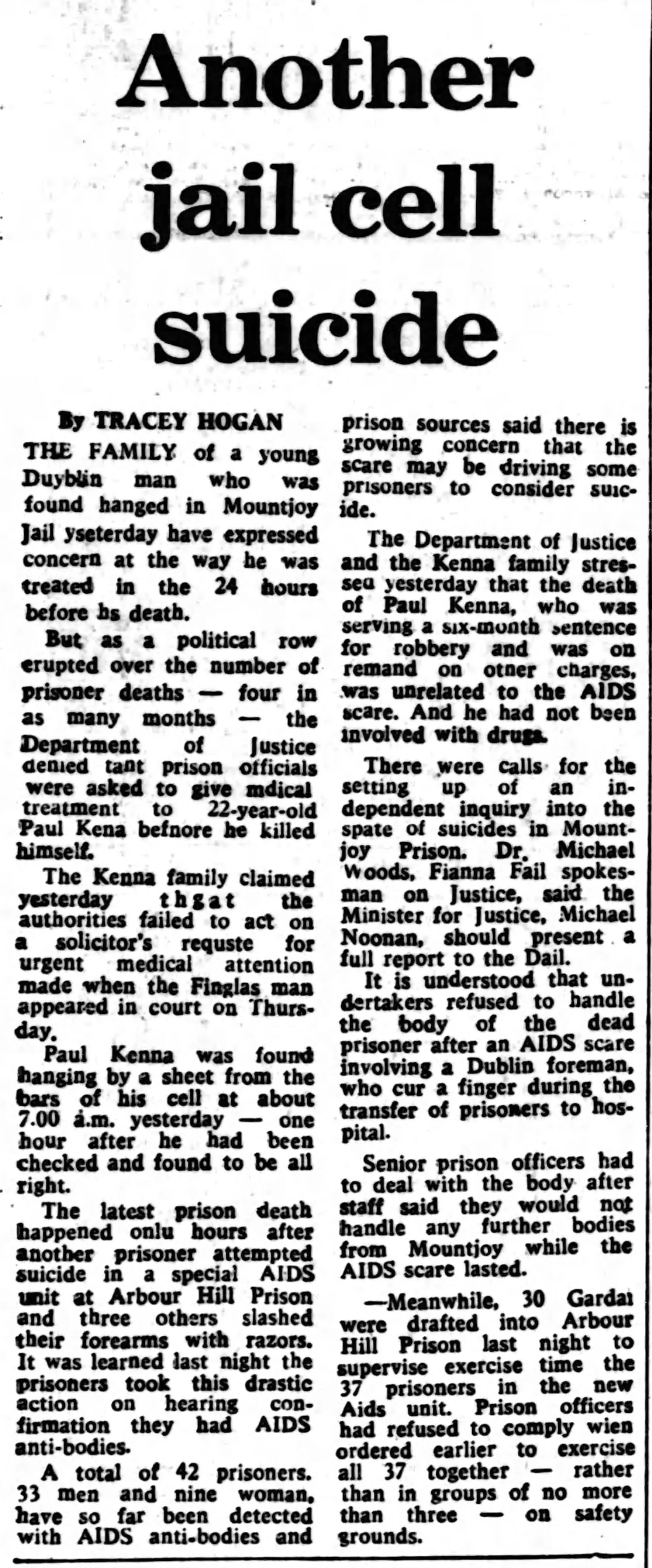

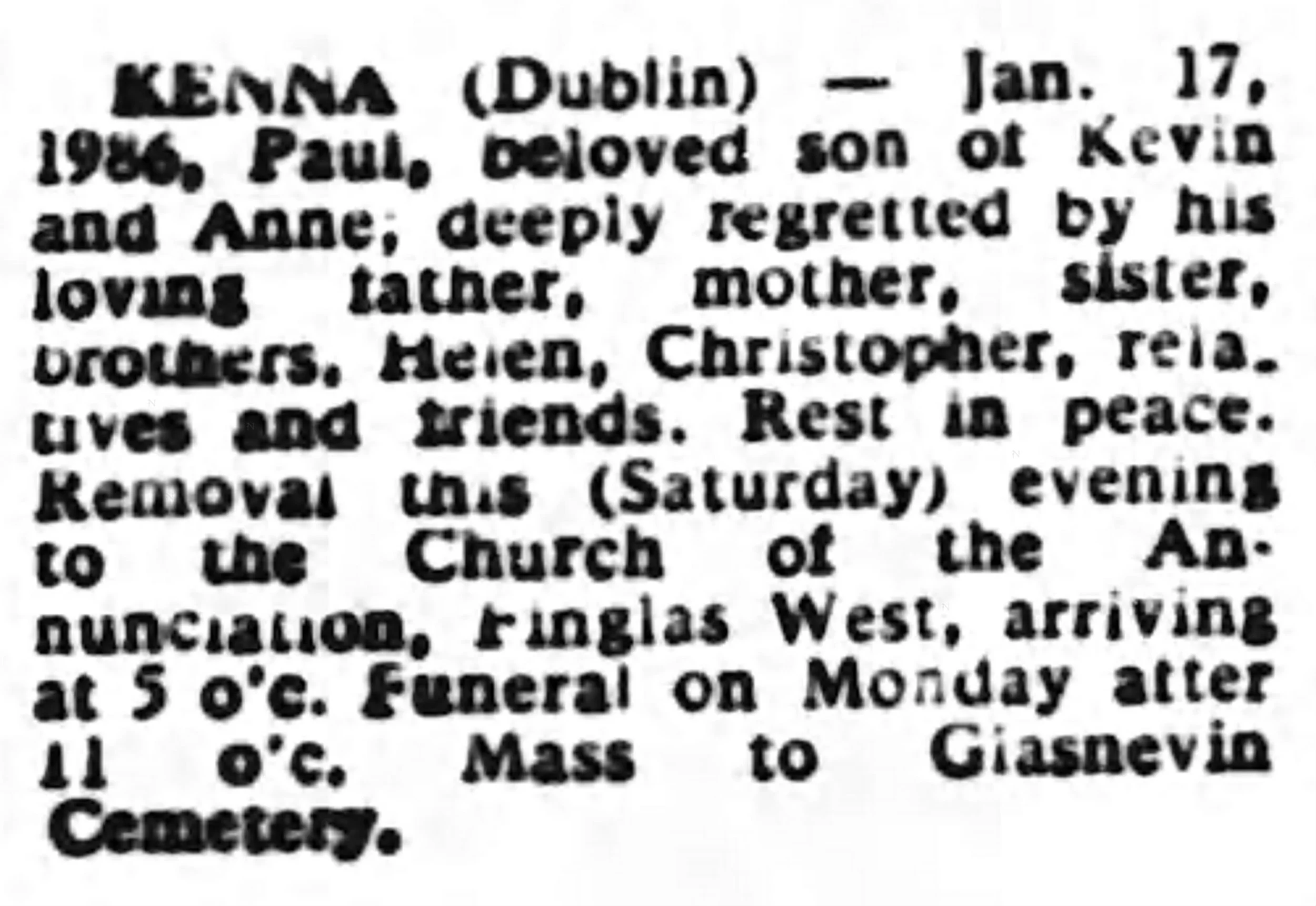

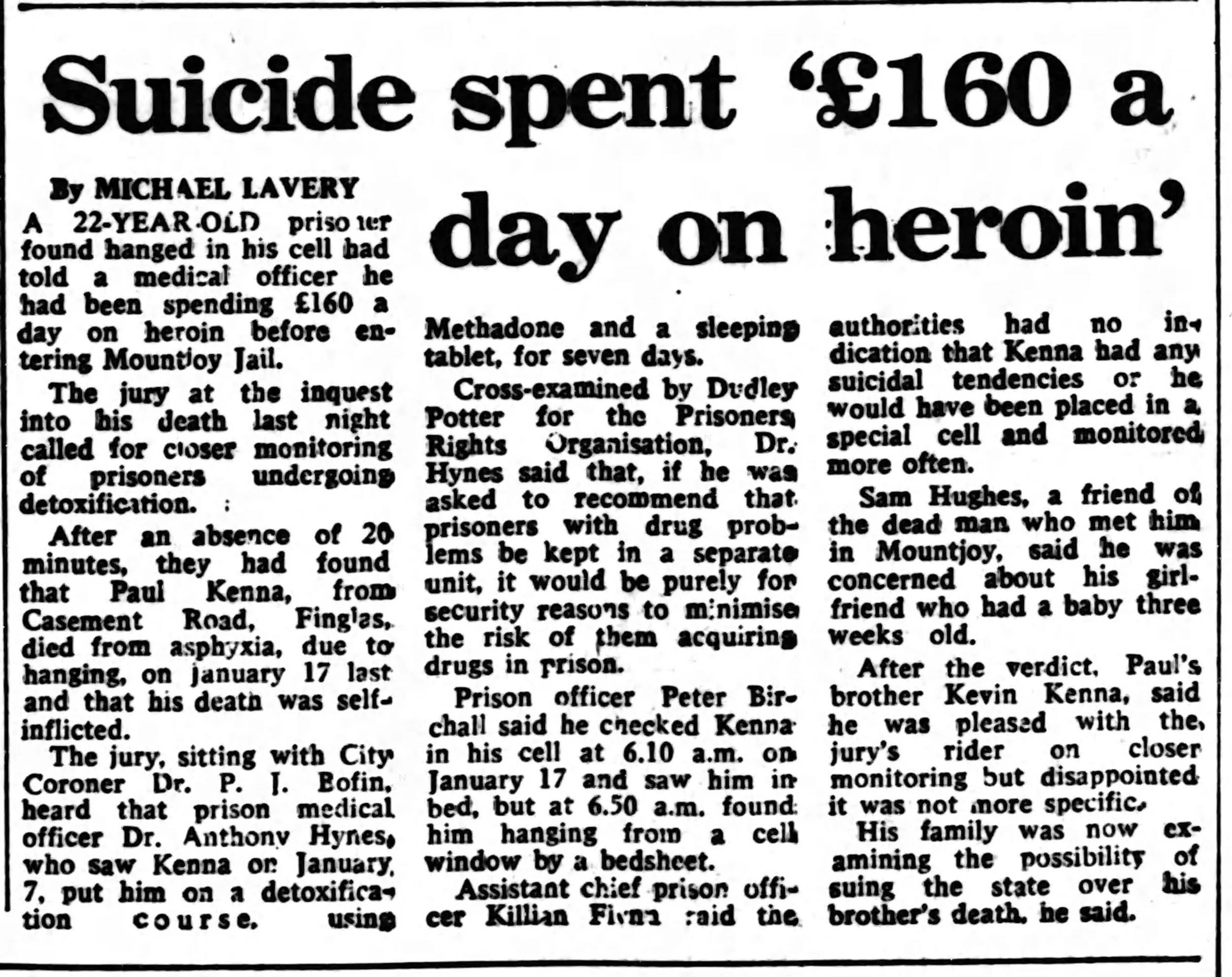

Paul Kenna, 22, was not confirmed nor suspected as having ‘AIDS Antibodies’ [HIV] but had seemingly taken his own life upon being incarcerated and having struggled with drug addiction.

Paul’s family used a press conference to counter initial official denials that he had been a drug addict, saying he had in fact struggled with addiction and had sought help. They argued that authorities and the prison failed him by not providing adequate support during withdrawal, a lapse they believe contributed to his death.

The timing compounded the tragedy: by January 1986 Ireland was still reeling from the so‑called ‘AIDS scare’ after a large number of prisoners had volunteered for HTLV‑III (then described as the ‘AIDS antibody’) testing in November 1985, with many subsequent positive results in January 1986. That panic, sadly, led to stigmatising behaviour — notably an undertaker’s refusal to remove Paul’s body from the prison, not because he himself had tested positive but through association with other inmates who had — an appalling fact that exemplifies how fear and institutional failures compounded the families loss.

Raymond was widely reported in the Irish press as having been taken to Richmond hospital unconscious from Arbour Hill’s AIDS separation unit. His mother spoke on RTÉ News, saying her son had overdosed on prescription drugs but insisting he had not taken them himself. The reports prompted a wave of concern and questions about safety and supervision within the unit, and about how a man in Raymond’s condition came to be exposed to medication, allegedly, not self-administered.

Days later, Dublin’s Evening Herald reported on 20 January 1986 that Raymond and another prisoner having been taken to Richmond hospital unconscious; “Both were being prescribed medication at the time and tests were being carried out at the Richmond Hospital in an effort to establish the exact cause of their illnesses. Both were being returned to the unit [Arbour Hill Prison AIDS unit] today”.

Ray, having survived and returned to the AIDS separation unit at Arbour Hill to serve out his sentence, reappeared in public records on 22 July 1999 when the Evening Herald in Dublin reported he was back in Mountjoy Prison and, along with several other inmates, had lodged a claim against the Prison and the State for “shock” and “trauma” after a fire in a neighbouring cell. Little more was learned of his later life except that he died on 13 December 2009 and was laid to rest with his parents and family in a family grave in Glasnevin Cemetery, Dublin. The one solace in the timing of his passing — despite being only 43 — was that Ray had been able to take advantage of HIV combination therapy from 1996, which prolonged his life for more than a decade at a time when an “AIDS antibody positivity” diagnosis in 1986 would, on average, have meant little chance of surviving past 1996.

DAVID TYRRELL

Rooftop Protester & Voice for AIDS Prisoners

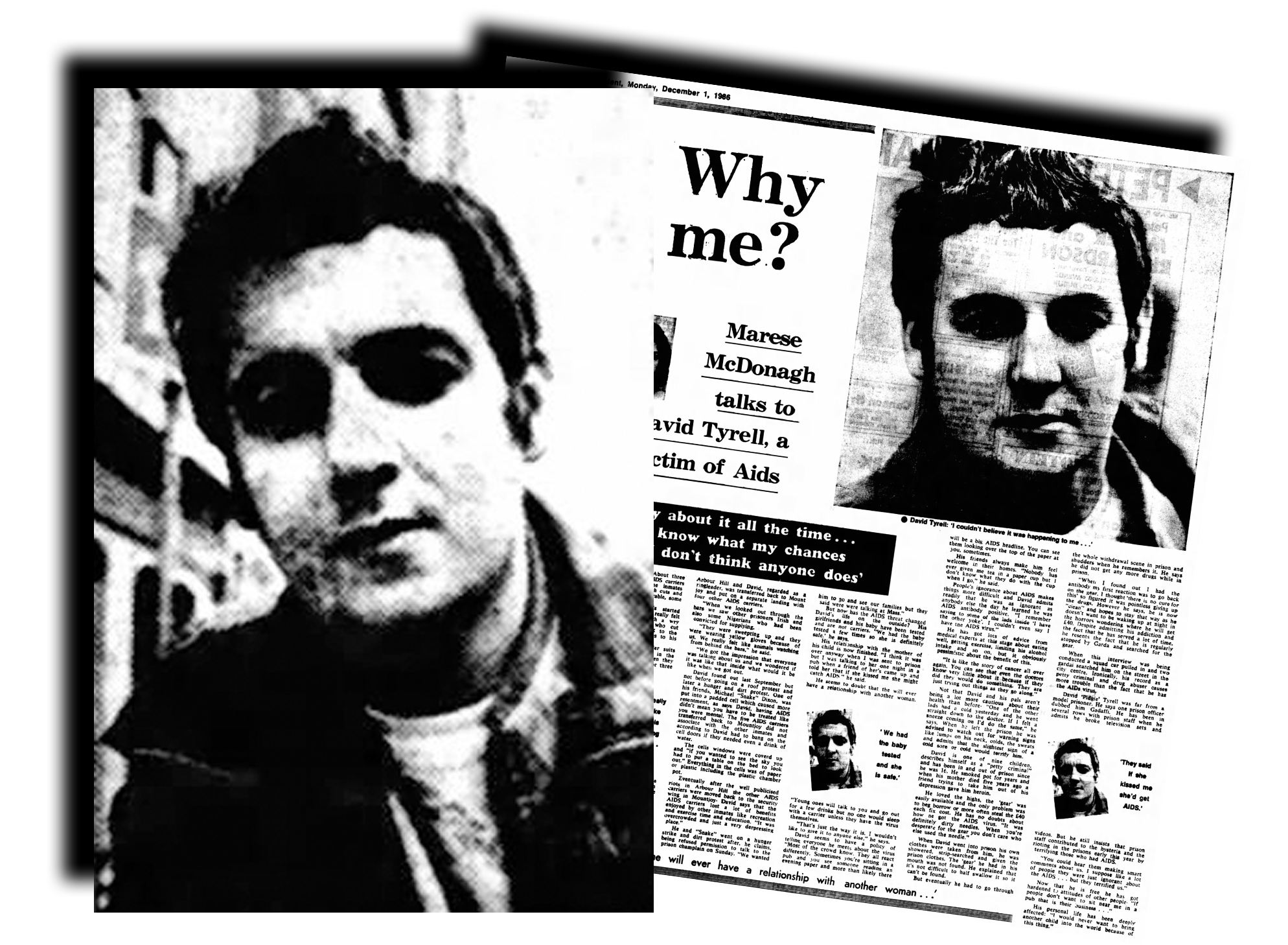

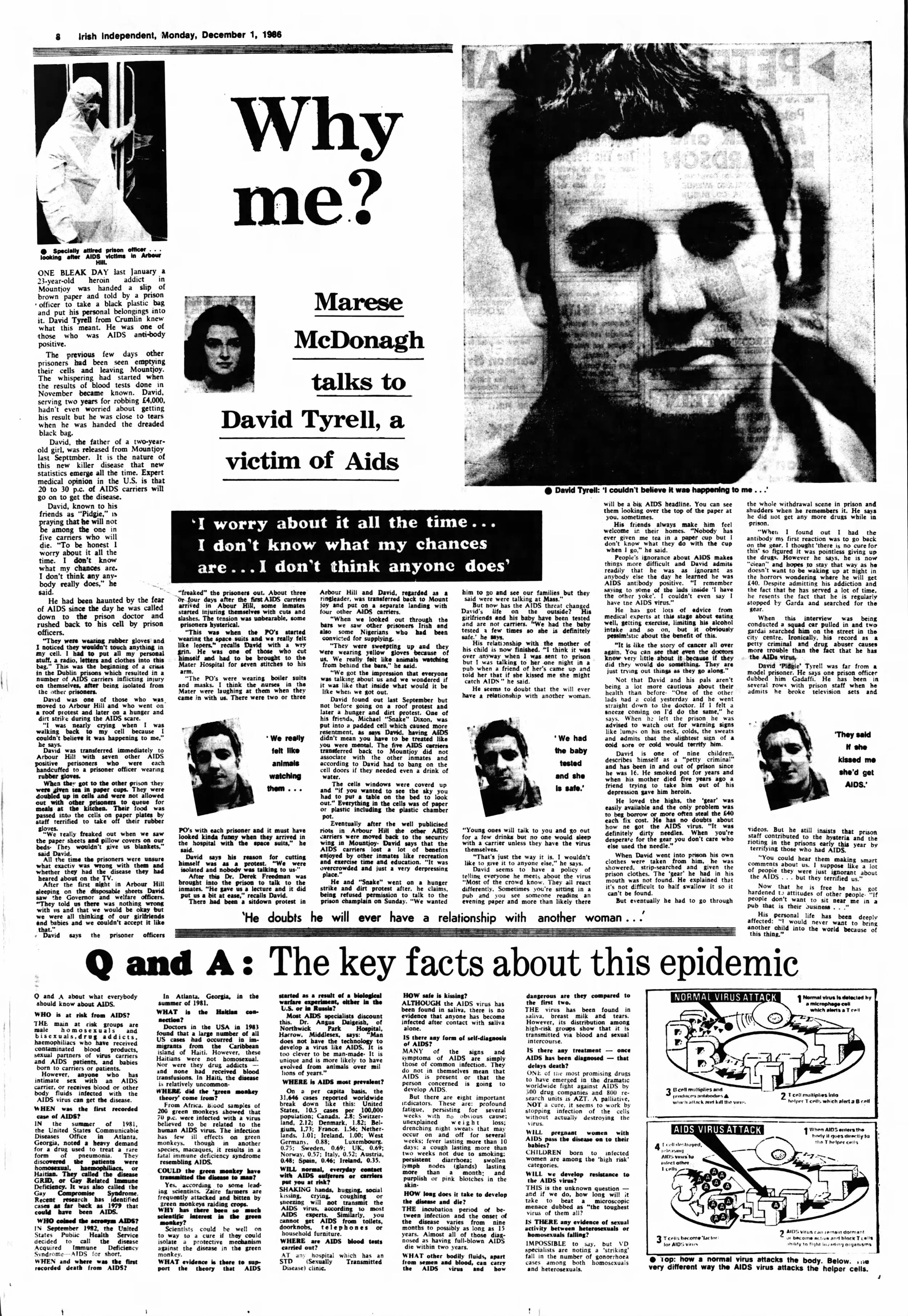

David had several convictions and, for a time, struggled with drug addiction, yet within the confined world of prison he unwittingly became a potent voice for change. When he and other inmates were told they were “AIDS antibody positive,” fear was his first reaction, as he later recalled in an interview on World AIDS Day 1986, but that fear did not stop him from standing up for himself and his fellow prisoners with the same diagnosis.

Their protests against appalling treatment were at times dismissed by sections of the public as hooliganism, and prison staff labelled David a ringleader and moved him accordingly — yet their actions were far from disorderly troublemaking. By insisting on dignity, medical care and humane conditions, David and his fellow prisoners exposed a systemic failure that ultimately forced reform and markedly improved the treatment of incarcerated people with HIV/AIDS. The paradox is stark: though imprisoned for wrongdoing, they did extraordinary good from inside the system, securing fundamental changes that ensured those serving sentences would receive the same HIV/AIDS treatment and care they were entitled to, just the same as those on the other side of the bars.

GEORGE CUMMINS

Prison Escapee living with AIDS

Dublin had long been plagued by a growing drug problem, and George’s story was far from unique: while serving time in Mountjoy for offences committed to feed his addiction, he learned through IV drug use that he had tested “AIDS antibody positive” and was transferred to Arbour Hill Prison’s ‘AIDS Separation Unit’.

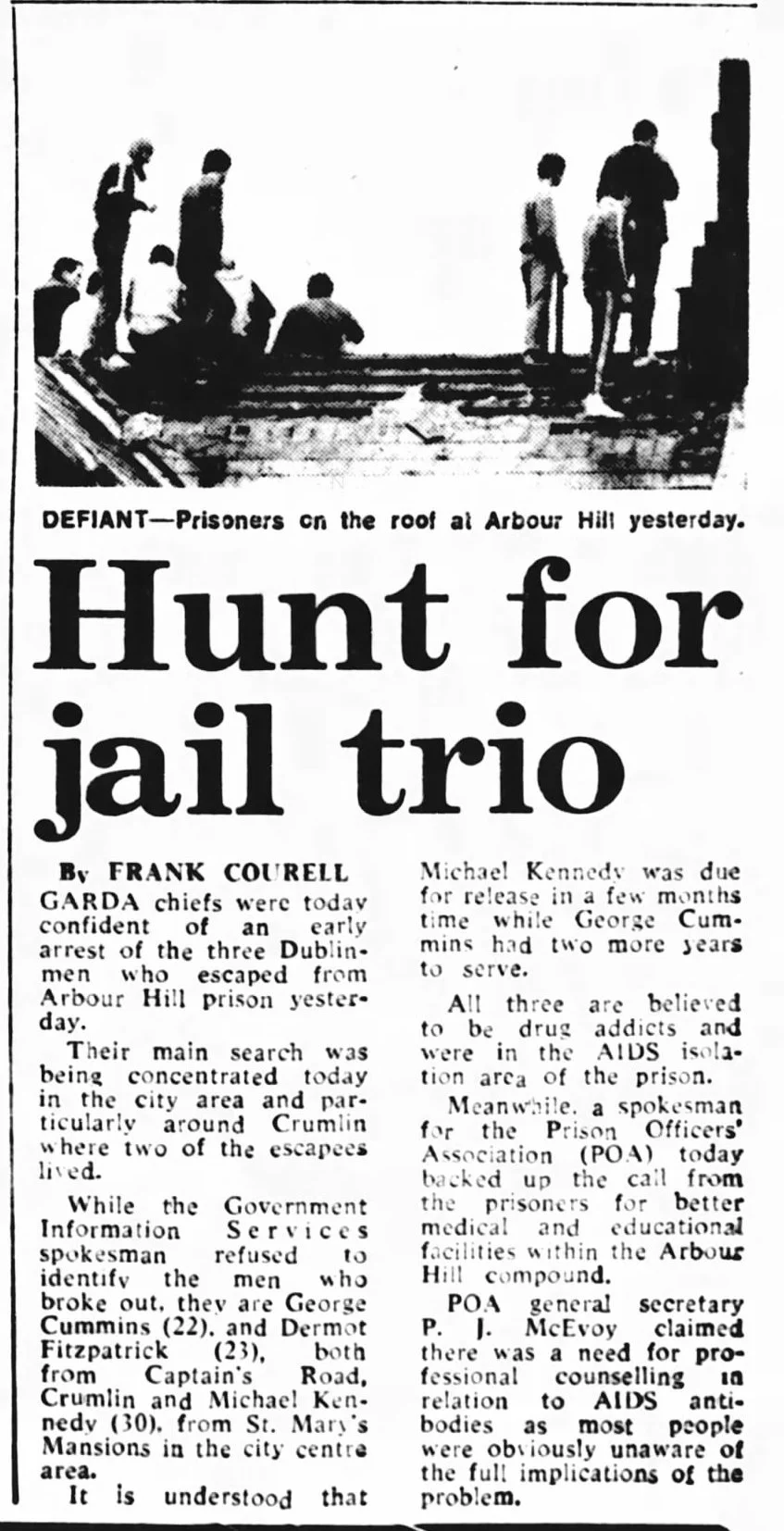

When a rooftop protest erupted atop the prison’s AIDS separation unit, George and two others seized the chance to slip away; his freedom lasted only weeks, as Gardaí tracking the trail of an armed bank robbery soon led them to George’s whereabouts.

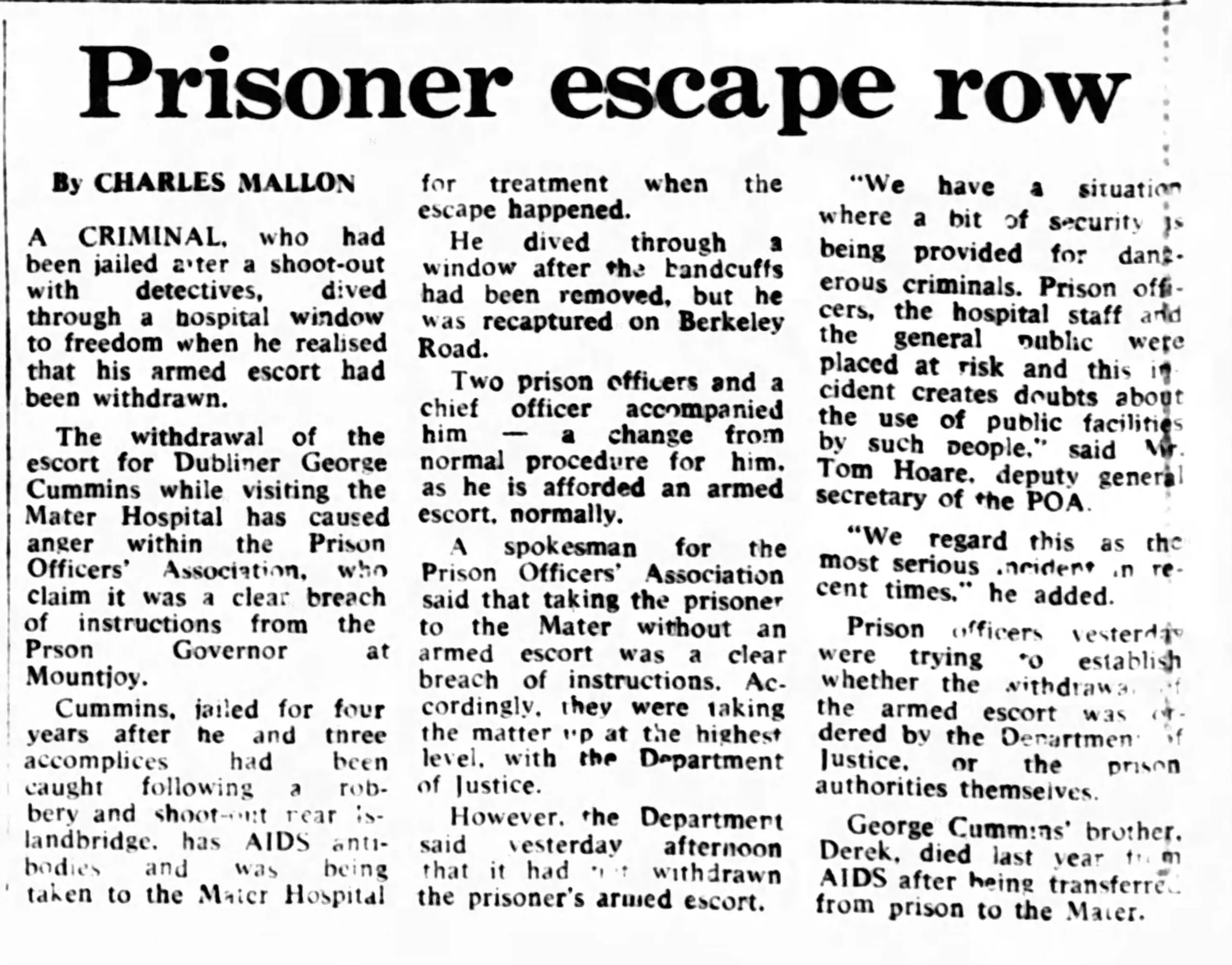

Back in custody, George’s health deteriorated and he began receiving care at Jervis Street Hospital as AIDS steadily compromised his immune system. In January 1988, during one of those hospital visits, he made a desperate bid for freedom by jumping through a window, but was re-arrested almost immediately.

He did secure early release, but it was sadly as his life was nearing its end. Geroge passed away of the 29th December 1991 at the age of 27.

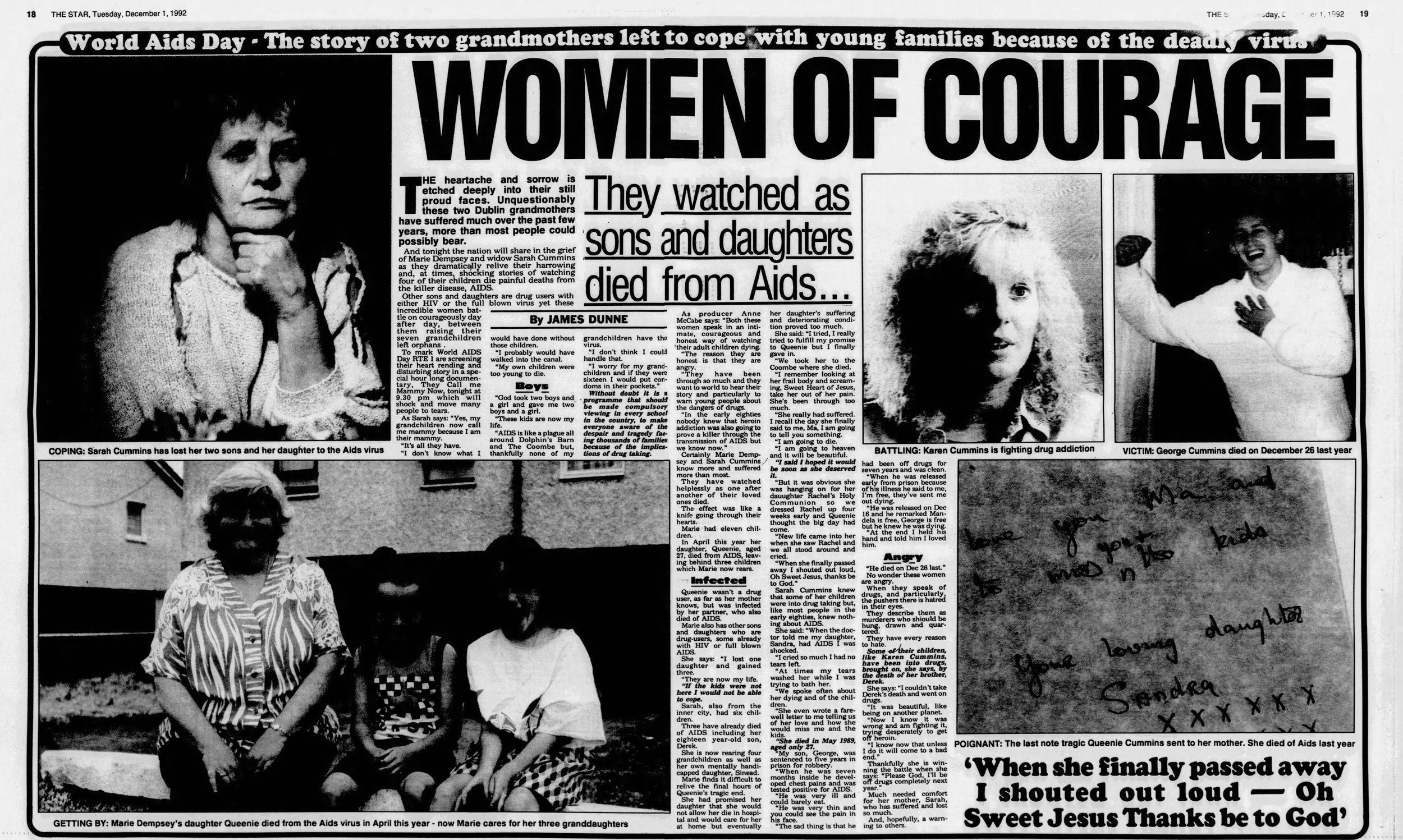

Mother Sarah Cummins carried the weight of unimaginable loss with a quiet, steadfast dignity—three of her children taken by AIDS.

Derek, who died aged 20, and his older brother George, who passed at the age of 27, both contracted HIV through intravenous drug use. Their sister Sandra died at the age of 27, believed to have contracted HIV from a partner who had already died from AIDS-related complications linked to IV drug use.

MICHAEL KENNEDY

Prison Escapee Living with AIDS

We are still researching and verifying insight to ensure we share accurate information

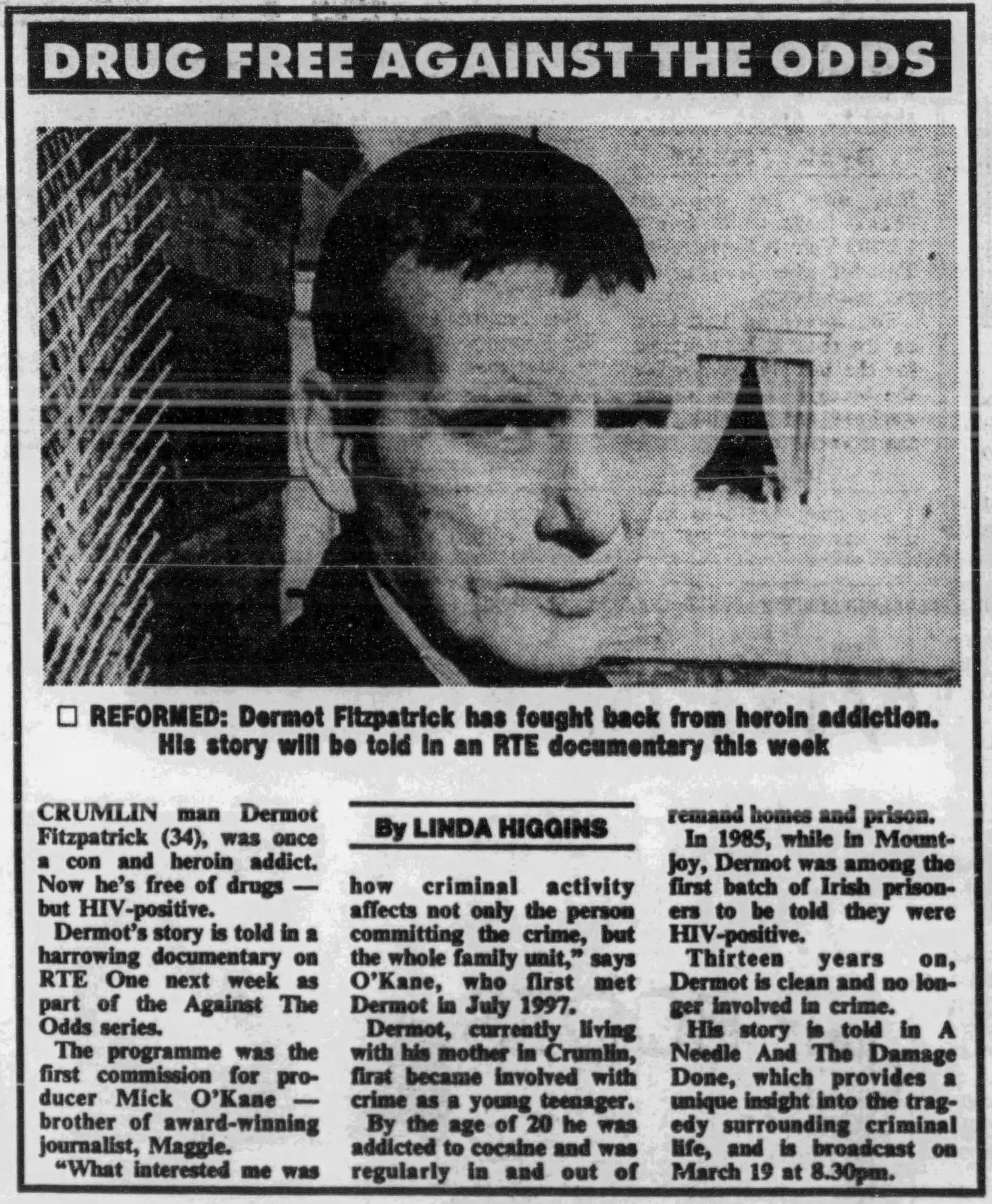

DERMOT FITZPATRICK

Prison Escapee, Drugs & AIDS Advocate

Dermot Fitzpatrick was one of the men transferred from Mountjoy Prison to the Arbour Hill “AIDS Separation Unit” and was among the three who escaped during the rooftop protest in March 1986.

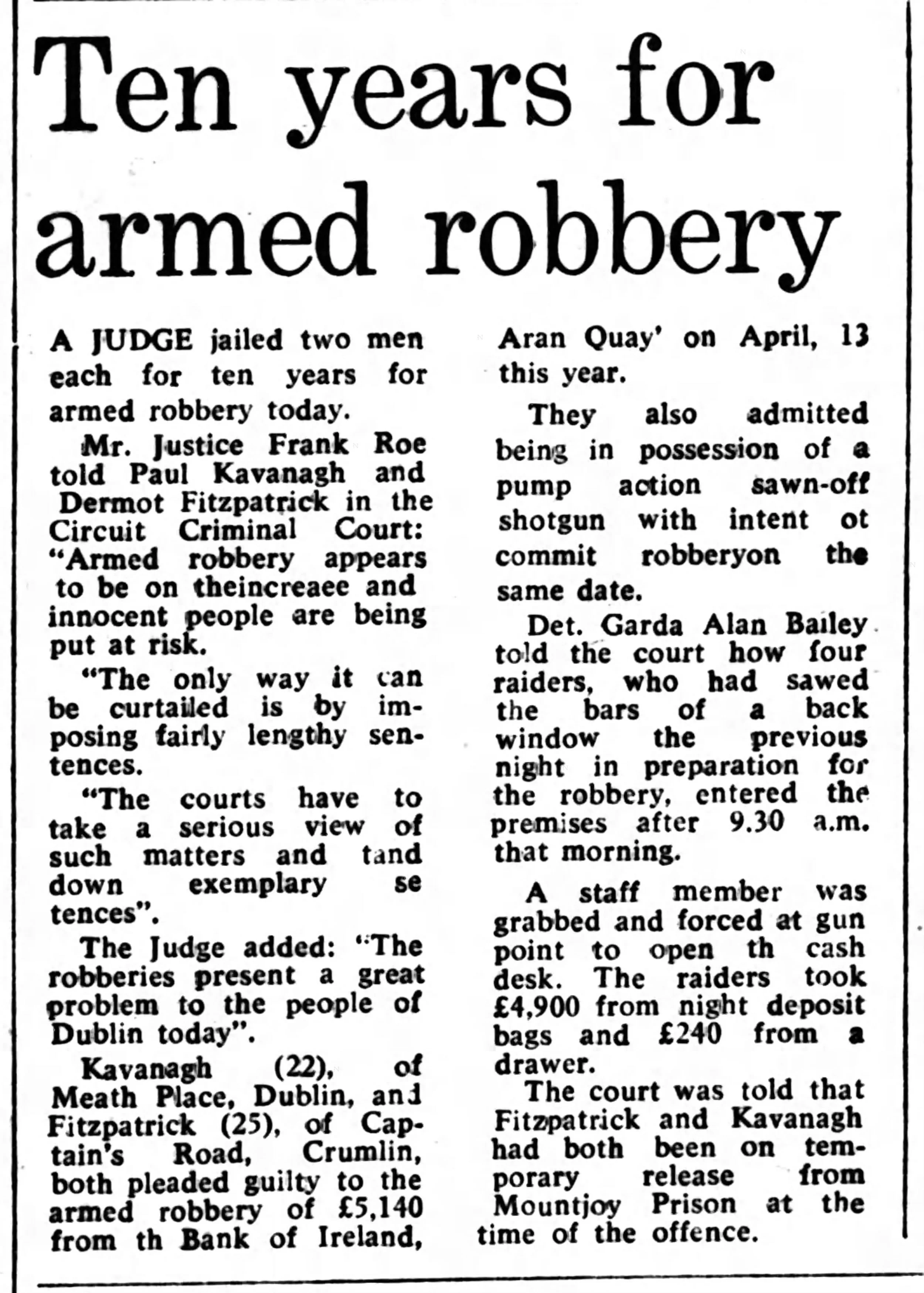

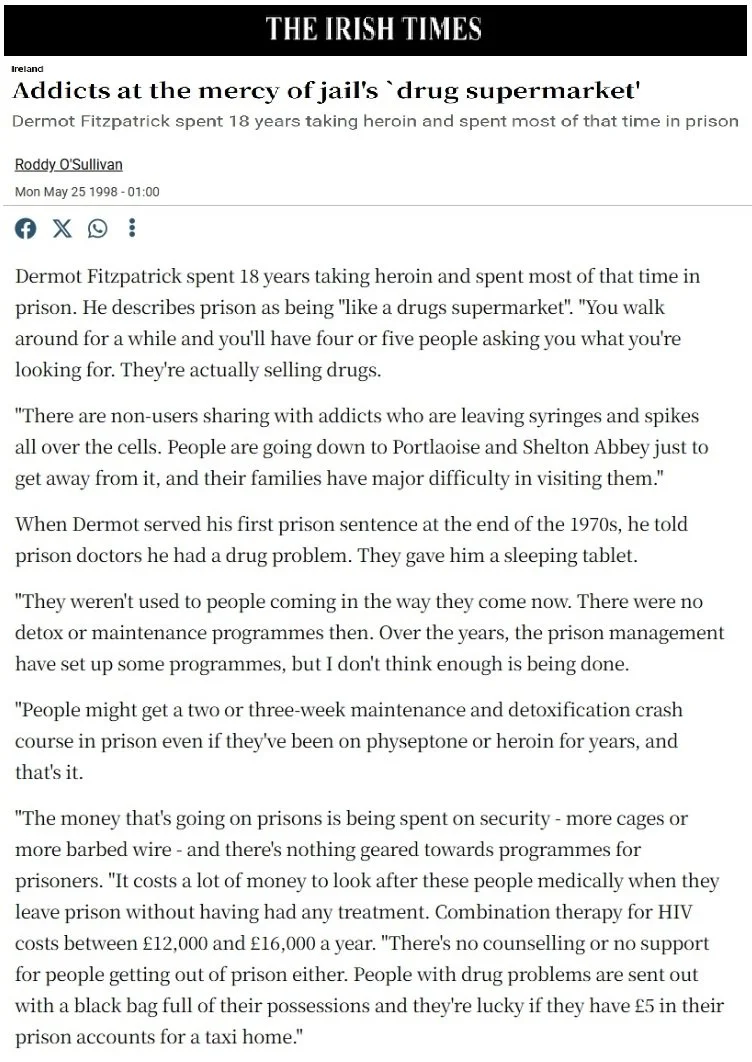

Recaptured and released on licence, his ongoing drug addiction later led to involvement in an armed bank robbery for which he was sentenced to ten years; after serving six years he was released and resolved to change his life. Dermot became drug-free and campaigned for effective drug rehabilitation for prisoners, determined to break the cycle of addiction, crime and incarceration, and he was forthright in criticising the authorities and the justice system for failing to provide adequate treatment. He spoke candidly to Ireland’s national broadcaster RTE in a documentary about living drug-free while HIV positive and about his commitment to educating young people on the dangers of drug use.

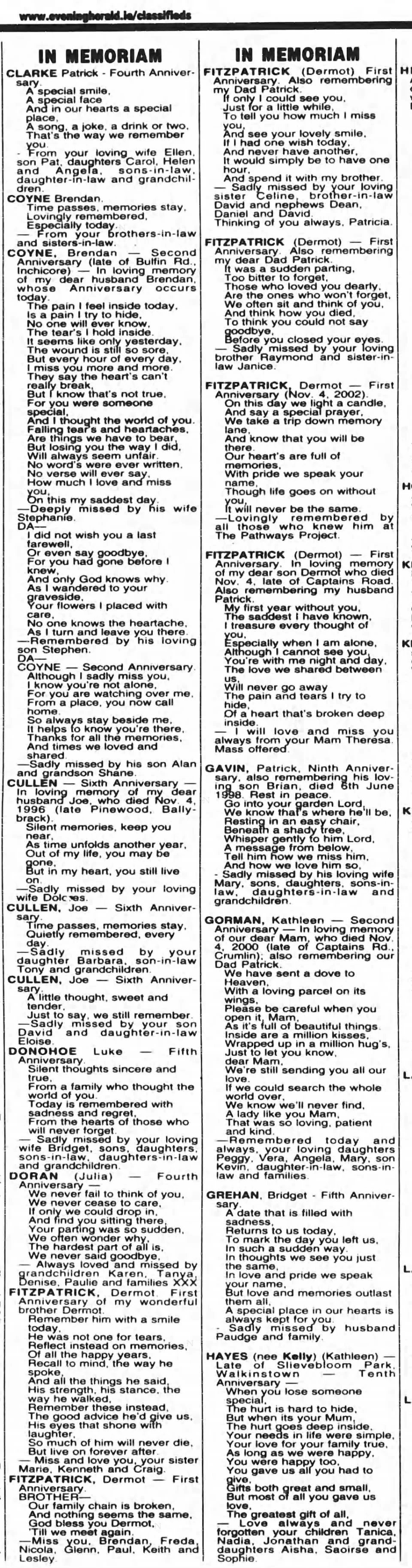

Dermot lived long enough to begin effective HIV antiretroviral therapy when the life‑saving combinations became available in 1996, a development that gave him renewed hope and extended years he might not otherwise have had; despite these advances, he succumbed to AIDS‑related complications in 2001 at the age of 37.

Any third-party copyright material has been accessed through paid membership or incurred an administrative cost. Material has been used under the ‘fair use’ policy for the purpose of research, criticism and/or education, especially around the topic of HIV/AIDS. There has been no financial/commercial gain.